"A fetish: somehow": A Sylvia Plath Bookmark

In 2008, I started a project to put together, in one place, a catalog of all the books that Sylvia Plath owned and read. Plath's "library" is dispersed, with the majority of volumes held in the special collections at Emory University, Indiana University at Bloomington, and Smith College. Smaller holdings can be found in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library, University of Louisville, University of South Carolina, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and the University of Virginia. Some books are still held privately.

Assembling Plath's library led me to read not just all of her letters and journals, but also the papers that she wrote for school. Using the social book site, LibraryThing, the Sylvia Plath Library now lists more than 1,200 books that the poet and writer worked with in her lifetime. It has not always been possible to determine the exact edition that Plath read, but at the least we have the titles.

As a matter of routine practice, I search for Sylvia Plath books to highlight on my Sylvia Plath Info Blog or to simply tweet out. These books are generally first or rare, limited editions that I intend to entice book collectors, libraries, or Plath enthusiasts to purchase. Spending other peoples' money is often easier on my conscience than spending my own. For example, in July 2016, a tweet of a unique Plath-Hughes family-owned first edition reprint of The Bell Jar (1963) led to the University of Victoria, British Columbia, acquiring it. An instance where social media positively benefited cultural heritage. In late November 2016, an equally seductive copy of a book came on the market about which I was instantly torn in two. My first impulse was to tweet it out and let some lucky higher education institution obtain a very nice object. But then I thought that perhaps it might make a nice treat for me to myself. My good friend and fellow Plath scholar Gail Crowther wrote saying it would be a nice present for such a big year: getting the manuscript of The Letters of Sylvia Plath, which I co-edited, submitted, and, though she did not mention it, also getting our own book of essays, These Ghostly Archives: The Unearthing of Sylvia Plath, to the publisher. This was sound logic, so I decided to jump on it.

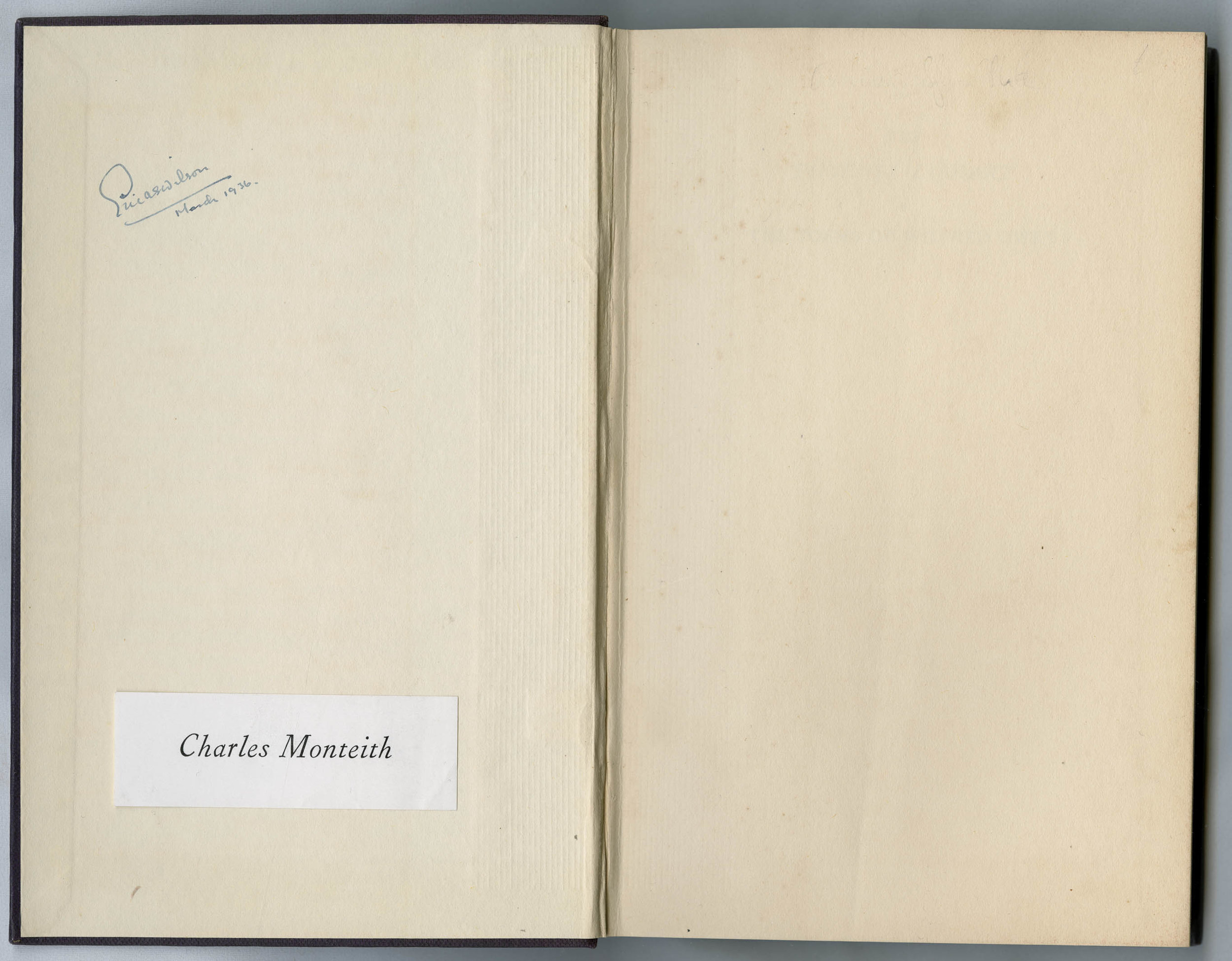

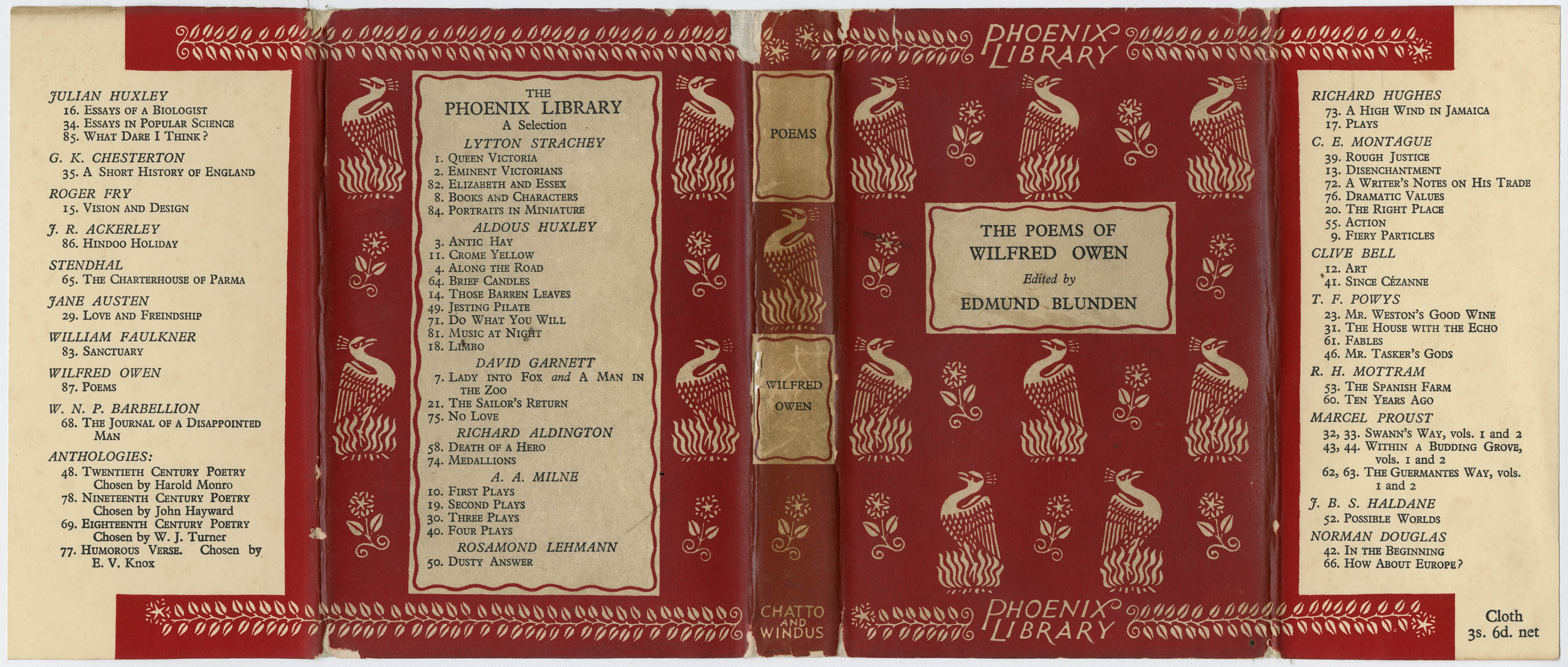

The book was The Poems of Wilfred Owen (London: Chatto and Windus, 1933) and formerly belonged to Faber and Faber editor and chairman Charles Monteith (1921-1995). Monteith was Ted Hughes' first editor at Faber and Faber, and in the course of that editorship he and Plath met on several occasions between 1957 and her death. On 23 June 1960, Plath and Hughes attended a cocktail party at Faber's for W. H. Auden. The next day, Plath wrote to her mother:

During the course of the party Charles Monteith, one of the Faber board, beckoned me out into the hall. And there Ted stood, flanked by TS Eliot, WH Auden, Louis MacNiece on the one hand & Stephen Spender on the other, having his photograph taken. 'Three generations of Faber poets there,' Charles observed. 'Wonderful!'

Monteith thoughtfully sent Plath flowers after her appendectomy on 28 February 1961. After Plath's death, Monteith became her editor when Hughes moved The Bell Jar and The Colossus and Other Poems (1960) from Heinemann to Faber.

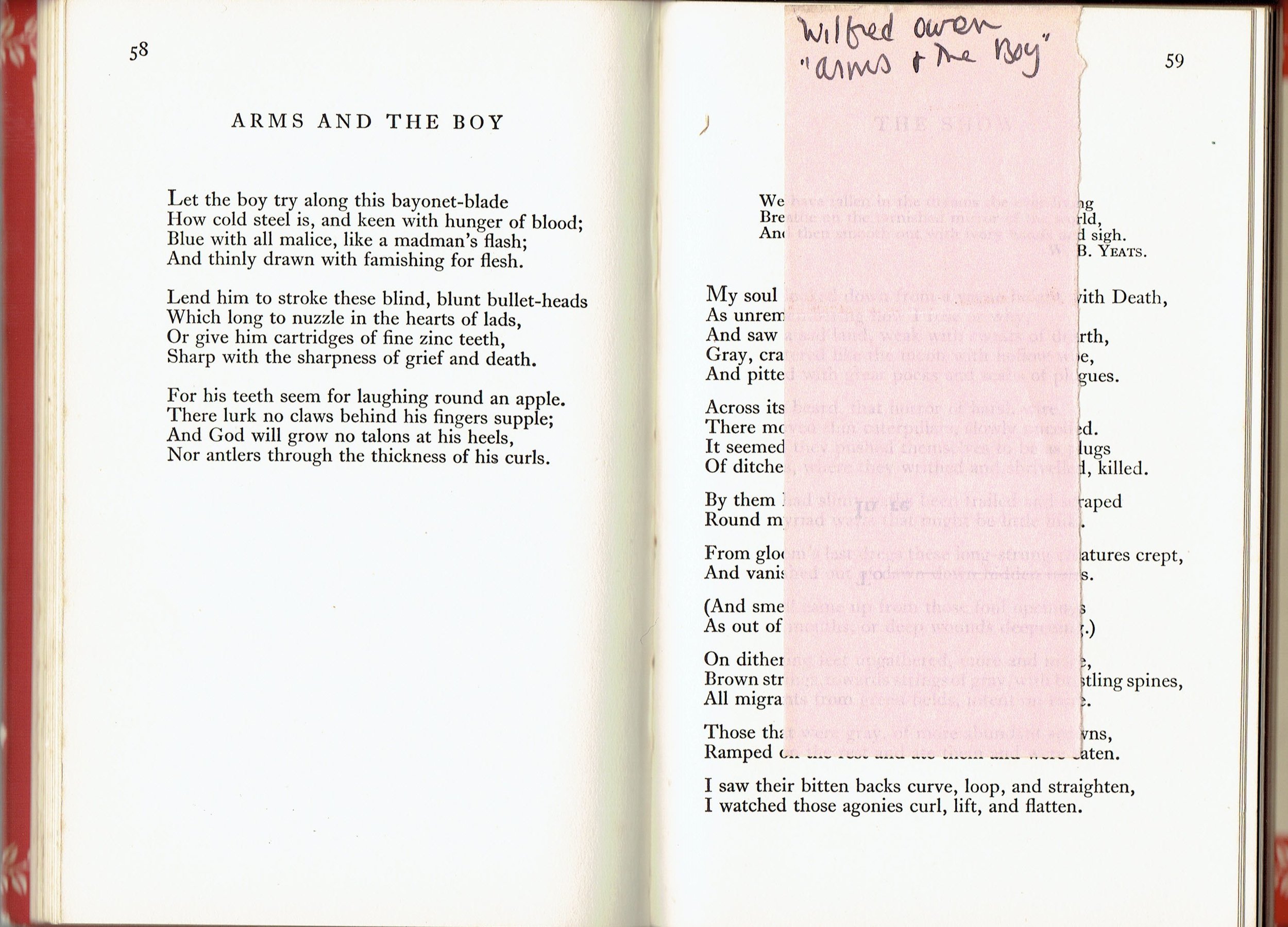

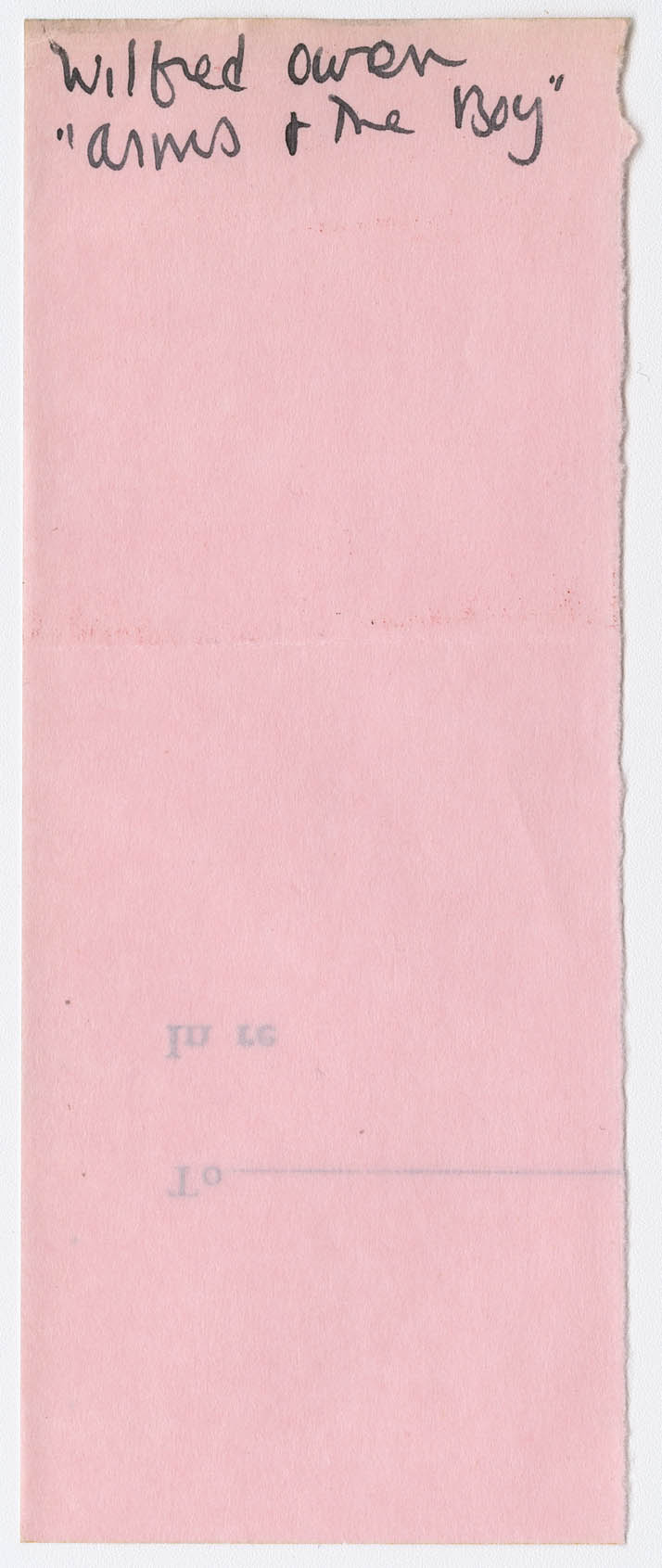

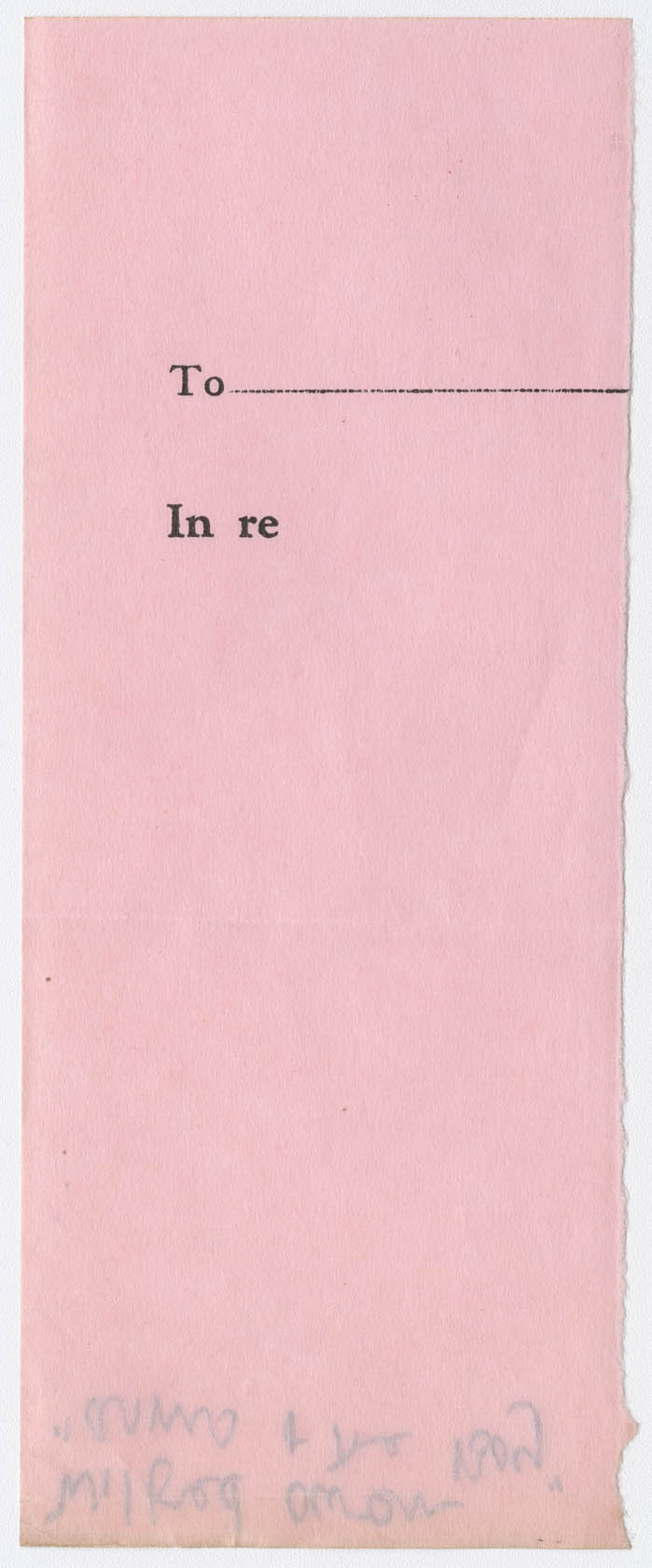

What makes this copy particularly special is that tucked between pages 58 ("Arms and the Boy") and 59 ("The Show"), on a piece of pink Smith College Memorandum paper, is a holograph note in Plath's bold black pen that reads "Wilfred Owen / 'Arms & the Boy'."

It is something to own anything in Plath's handwriting and something even more special that it is on a sheet of her famously fetishistic pilfered pink paper. Plath taught three sections of Freshman English at Smith College in the 1957-1958 academic year. After deciding to leave teaching to live and work as a full-time writer in Boston, Plath began stealing the pads of paper from a supply closet in one of Smith's academic halls. On 3 March 1958, Plath wrote in her journal:

Got a queer and most overpowering urge today to write, or typewrite, my whole novel on the pink, stiff, lovely-textured Smith memorandum pads of 100 sheets each: a fetish: somehow, seeing a hunk of that pink paper, different from all the endless reams of white bond, my task seems finite, special, rose-cast . . . & have already robbed enough notebooks from the supply closet for one & 1/2 drafts of a 350 page novel. (344)

A week later Plath wrote, "must be up early, to laundry & to steal more pink pads of paper tomorrow" (348).

Plath made the most of this pink paper. She used it in the fall of 1958 to type notes from her stint as a secretary in the psychiatric ward of Massachusetts General Hospital. From 1958 to 1959, Plath used it to type her journal notes after therapy sessions with her psychiatrist, Dr. Ruth Beuscher. Several letters to Jane Baltzell-Kopp (Cambridge classmate), Peter Davison (editor, former lover), Gerald and Joan Hughes (brother- and sister-in-law), Olwyn Hughes (sister-in-law), Aurelia Plath (mother), Warren Plath (brother), and in one instance, on a torn sheet, to accompany a poetry submission to Accent, were typed on this paper. Most famously, Plath typed drafts of her novel The Bell Jar on it in 1961, and reused the clean verso in drafting her Ariel poems. By June 1962, the paper supply was spent. Plath wrote to her former college professor and mentor, Alfred Young Fisher, on 11 June 1962. In this letter she asked him to send her "about a dozen" of the pads, offering to pay for them and enclosing a half-sheet sample of the paper for reference. She also sent a signed and inscribed copy of The Colossus (the American edition published by Knopf the previous month). Though it appears unlikely Fisher complied with the request, he retained everything and these documents are all held by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. When Smith College purchased their Plath collection in 1981 from Ted Hughes, Plath's stolen pink paper returned home. If you have ever worked with Plath's archive (sheets of this paper can be found in several repositories), chances are you too have seen this "lovely-textured" paper. If you have not, a simple Google image search will yield some examples.

A book such as this leads to speculation. It asks more questions than will ever be possible to be answered. Was this book originally Plath's and/or Hughes' and they leant or gave it outright to Monteith? Probably not. More likely, it was Monteith's to begin with and he leant it to them. The book is completely clean of markings save for an ownership inscription on the front endpaper which reads "Erica S[?] Wilson / March 1936." This suggests that Monteith acquired the book secondhand. On the front free endpaper, there is an erasure visible; what it originally read is vague. A 600 dpi scan reveals the words "[ ] Sylvia Plath" and a £ symbol. I tried adjustments in Photoshop but gave up and wrote the bookseller directly. He informed me that he had written "Ex libris Sylvia Plath" but then erased it prior to shipping (a common practice). There is no other proof (such as her name written on the front free endpaper, which was her typical practice) to actually suggest the book is from the personal library of Sylvia Plath.

Hughes and Plath both—but more strongly Hughes—were influenced by the poems of the World War I poet Wilfred Owen. Hughes published a poem, "Wilfred Owen's Photographs," in the 2 January 1959 issue of The Spectator, and later in his second volume of poems, Lupercal (1960). After Plath's death, Hughes wrote at length on Owen's "Dulce et Decorum Est" and other poems as he drafted a review of C. Day Lewis' The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen (1964).

In addition to speculation, the mind opens up to fantasy scenarios. Possibly Faber and Monteith were trying to put together a poetry anthology and asked Plath (and/or Hughes) to pick a poem for inclusion and this was Plath's choice? I searched Plath's journals and letters, but found no mention of her either working on or reading the poetry of Wilfred Owen. There is, though, some evidence that Plath took an interest in World War I. In a letter dated 16-17 August 1960, Plath wrote from London to her mother that she was finishing Allan Moorehead's Gallipoli (1956), the definitive history of this tragic campaign that killed a quarter-million Allied soldiers. (The Plath-Hughes copy of Gallipoli, which contains annotations, is held by Emory University.) Five days later, on holiday in Yorkshire, Ted Hughes sent a letter to Aurelia and Warren Plath saying that, "Tonight Sylvia got my Dad talking about his experiences in the 1st War . . ." (169). Her father-in-law, William Hughes, was a survivor of that battle. In his Ted Hughes: The Unauthorised Life (2015), Johnathan Bate writes that Mr. Hughes was "saved from a bullet by the paybook in his breast pocket" (33). It appears that Plath was on something of a World War I binge at this time, which in the absence of any other evidence or information, makes me wonder if it was during this time that she read the book and marked the page/poem.

The speaker in Plath's "Lady Lazarus" advises those who have come to view her 'big strip tease':

And there is a charge, a very large charge

For a word or a touch

Or a bit of blood

Or a piece of my hair or my clothes. (Collected Poems, 246)

Owning "a piece" of Plath is a privilege. Typescripts of her poems and stories can often sell in the thousands, or tens of thousands. Many of her drawings sold via the Mayor Gallery in London in 2011 and at that time I was fortunate enough to buy her drawing of a horse chestnut. It happened to be last drawing still available with her initials "sp" on it; an indication that it was something Plath deemed finished. This bookmark cost $250 which seems, to me, to be a fair and reasonable price even if just for a slip of paper. The book just came along for the ride, though there is also a feeling of specialness knowing she temporarily possessed it. Had her notation been on plain white paper I am not sure this would have such an allure to me. Being familiar with Plath's archive, with her love of that pink paper and the work that she created on its siblings, makes this a most cherished pink thing.

__________

NOTES: Digitized images of many of Wilfred Owen's poems are online via The First World War Poetry Archive. There are two manuscript drafts of "Arms and the Boy." The first draft features many crossed-out words; Owen slashed through the poem entirely. The second draft has just a few holograph corrections and is a much cleaner copy. These changes represent the final ones Owen made, thus making it completed. Additional poems can be viewed on the website of the British Library. For more, please see Tim Kendall's Modern English War Poets (OUP, 2009).All links accessed 30 November 2016 and 4 January 2017.