Thirteen Ways of Walking Home

I

So you’re home again. I’ve come back: no-longer-local woman returns home with intent to spend her Christmas Day retracing the footsteps of her hometown boy, Wallace Stevens.

The Wallace Stevens Walk is a 2.4 mile route winding from Stevens’ job in downtown Hartford, Connecticut to his home at 118 Westerly Terrace—a stone’s throw away from my high school.

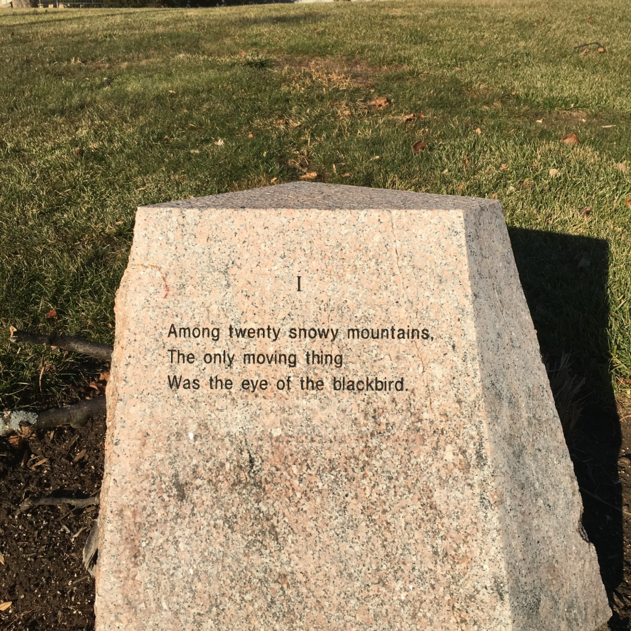

The walk is lined with thirteen stones of Connecticut granite, inscribed with each stanza from “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.”

I never read Wallace Stevens in high school. We never took field trips to his home or retraced his steps through the Rose Garden in Elizabeth Park; around the pond; over the footbridge; past the peeling paint of the greenhouses from his poems, which appear in the background of my adolescent photos—this park where we skipped Algebra to eat pancakes and dream, where the grass was full and full of yourself, where Stevens wandered seeking poems 60 years before.

I never even knew that Wallace Stevens lived there, there where I dreamt a little by the river, a local abstraction, until after I’d already left home.

Public acknowledgement is not the Connecticut way. We keep our quiet questions to ourselves.

II

Hartford—the entire city—is gray. Stevens—a poet “some Connecticut people have heard of but never read”—wore gray suits and worked in insurance, like all the fathers of my middle school friends. Retaining its old Puritan mannerisms and behaviors, Connecticut is not a place to be visibly unconventional. It’s a place where everything blends into beige and gray, where poets take a long time to find their way out of the snow that silently piles up against the windows.

I arrive in downtown Hartford in the early afternoon on Christmas Day and make my way toward the first granite stone placed along the route toward Stevens’ home.

I’ve never liked the blackbird poem. I don’t know how I’ll feel while reading it on stone,

on this walk today, but that’s why I’m here: I want to find my way into what Stevens might have felt while he wrote poems in our shared city of Hartford: I needed a place to go where I could be complete in an unexplained completion, where I could recognize my unique and solitary home.I feel the taste of Earl Gray on my tongue. I make my way down Asylum.

III

Wallace Stevens never learned to drive, and neither did I. We share this quietly radical approach to living. In Connecticut, driving is a quiet privilege while walking, like the writing life, is inconceivable. In Hartford, walking is as misunderstood as writing: neither can be quantified, and no one speaks of them. But walking ensures that the body’s rhythm aligns with the rhythm of the mind, and a writer must manifest pathways that do not obstruct the mind’s unfolding thought.

We found it in Hartford, Stevens and I. We found that walking generated a protective silence—an exterior manifestation of the topography of our questioning hearts; an anonymity surrounding us in our quiet gray clothing, opening out into the possibilities of the mind.

We passed the buckeye tree, the sassafras, the shingle oak; the Gothic brownstone church with bright blue doors, and we asked ourselves: Which of these truly contains the world?

Stevens walked from home to work and back again each day, composing poems with his footfalls, revising by retracing his steps through the quiet streets of Hartford: see the river, the railroad, the cathedral, while others watched him walking, so peculiar, through the quiet streets of Hartford, seen in a purple light.

IV

In the script of my life as an adolescent in Connecticut, I am and have a being and play a part.

I recognized the life I saw around me because I’d never known another kind. But some days, when it rained and I was trapped indoors with only the company of my own mind, or when the sun shone around the ivy-covered gazebo in Elizabeth Park, I thought that maybe there could be another life out there for me, quite possibly. Where would I find it?

Was it out there, really, somewhere far away from all this granite stone? It would be enough if we were ever, just once, at the middle, fixed In This Beautiful World of Ours and not as now, helplessly at the edge. What things, in my life then, were Fixed in the mind or at the middle?

Not me, not I, not whatever my Self was. Maybe the leaves, whirling in the trees, collecting my questions, scattering them swiftly in the wind.

Some pantomime. Back then I was an actor, thought the stage would set me free.

V

Although you sit in a room that is gray, Wallace, I know how furiously your heart is beating.

I don’t know how you lived and wrote poetry each day in this city that always seems so gray, even in summer. It doesn’t sound like you were happy.

Your daughter says that, growing up, despite the holly bush you planted at the house in honor of her name, she wasn’t happy. Your wife, Elsie, hated your poetry. She wasn’t happy.

What made you happy, Wallace? Escaping the gray landscape of Connecticut for the lush saturation of Key West? Getting drunk and punching Papa Hemingway in the face? Coming home to Hartford and eating a silent, private meal alone at a table inside an exclusive club where you spoke to no one? It doesn’t add up—this personality plus the silence of your poems.

What were you looking for, in life and in your poems? It can’t have been beauty—not only that.

I think it was more that you were seeking—not beauty, but the silence following beauty.

VI

His life was indecipherable. I can’t comprehend it as narrative, even while I feel I understand its hidden essence. I want the story behind the story; the one he never shared, not a critic’s analysis or biographer’s interpretation. I want to know why no one in Hartford knows about Stevens—only Mark Twain, only Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose museum-houses lie just down the road. Stevens—he disappeared beneath the sidewalks, beside the pond in the park. He worked in Imagism, capturing an image from multiple lenses, beyond the contours of a realistic view. It was a language he spoke, because he must, yet did not know. His poems are an endless philosophical question: the nature of being; how we find ourselves in the places where we find ourselves to be; how to bring articulation to the grayest confusion; of what was it I was thinking? So the meaning escapes, always tracking the meaning, tracing the concept, circling the question.

VII

O thin girls of Hartford, O skater boys of Hartford, what will you discover when you take yourselves out to the church basement punk show? When you visit the makeup counter at the mall? Do you not see how the rhythm of Hartford is a performance all its own? It is deep January. The sky is hard. Where did you go? This city needs you. The roses in the garden reach out for you. The birds are waiting for you to name them. I could not bring myself to.

You’ll have to stay, because I signed some metaphysical contract that says I need to go, to be free again, carry me to the cold, go on, go on, plunge on.

If you’re going, I will not watch you go. The snow flies upwards at an angle.

VIII

In taking this walk with Stevens—which I’m sure he never imagined anyone would copy—I’m trying not to hold any unrealistic expectations for a grand, transformative experience.

I’m hoping to feel differently about the blackbird poem by the time it’s over, but I’ll be happy with any inspiration that flies my way. Maybe I’m looking for some validation for being a writer from Connecticut, looking for the poem of the mind in the act of finding what will suffice.

When I reach stanza 8, just past a bridge above the river I feel sure that Stevens paused along each day, my phone dies. Suddenly I feel ill-equipped to be here. What if I can’t find my way home? Connecticut is not a place where you can knock on someone’s door on Christmas Day: hello, can I charge my phone? But stanza 8 is one of my favorites, so I tell myself it will all work out somehow. The abstract was suddenly there and gone again. It had been real. It was not now.

I grasped it only briefly: this essence of what Hartford meant to me. The rhythms that shaped me, the syllables we swallow in the middle of words.

IX

Part of me imagined I would live here in Hartford one day, as an adult. I’d settle down in one of those historic row houses in the West End. My home would be full of books and antiques, dark wood, mahogany—the sound of it, the word; it’s always sounded full to me, like silence. Like Stevens, I’d live in walking distance to Elizabeth Park. As long as I had a cloistered writing room at home, I wouldn’t need much else. A simple window on the world. A sidewalk of poems, leading to the park. I would wake in the morning indoors where the world was beyond my understanding. But when I walk I see that it consists of three or four hills and a cloud.

A poetic existence. Living as a poem. Living inside a poem—that’s what I wanted. It’s what I wanted to be. But Poetry, I’ve learned since then, is the supreme fiction. I can’t go back again.

X

With my phone dead, passing the wealthiest homes in the city of Hartford, I’m beginning to feel conspicuous—more visible. I’m afraid that all the parents of my middle school peers will drive by and see me walking down the road on Christmas Day like I’ve got nowhere to go. They won’t roll down their windows to call out to me. They’ll shake their heads at one another and say, There was always something strange about that girl. Because the houses here, the people, none of them are strange. They’re not going to dream the way I do, so I try to stay away.

I’ve heard about this happening to Wallace Stevens as he was walking home: caught in the rain without an umbrella, strolling along, some woman he knew from somewhere pulled up to the curb and rolled down her window, Why Wallace, you mustn’t drown out there in the rain for goodness sakes, come inside, get in the car, I’ll drive you home.

Alright, he said to the woman in the car. But only if you’ll let us drive in silence. And I would say the same, if anyone stopped. To have a conversation at that moment: it would be an irretrievable interruption. I’d never get the moment back.

XI

I turn on Wallace Stevens’ street, Westerly Terrace. A couple emerges from a house on the corner with their dog. They pass by and we say hello, how are you, Merry Christmas. The sky is blue; it is darkening. The difficulty to think at the end of day.

Stanza 11 is buried in the bushes and the brambles of a family home. I draw close to it; focus my eyes on it. I try to focus my mind, but I feel myself wandering.

This walk, the scenery, my experience on the street: So that’s life, then: things as they are? What was I hoping I would find? Where was it one first heard of the truth?

XII

I’ve been walking for over two miles now. Stanza 12 is perched on the grassy median between the looming houses on the street. I feel conspicuous. I feel the Christmas fires burning in the living rooms inside and my self not near them. I taste the Christmas cookies and the Christmas wine I do not eat and drink but only imagine. Too much as they are to be changed by metaphor, too actual, things that in being real make imaginings of them lesser things.

Things like the Christmas meal my mother is cooking back home while I walk: turkey with stuffing, biscuits, plain and sweet potatoes. I taste them. I do not taste them.

XIII

From atop the grassy median, I squeeze a final breath of battery from my dead phone, enough to take one picture of Stevens’ large Colonial home across the way, which is not a museum but simply someone else’s home.

I read the text imprinted on the thirteenth stone and for the first time, I hear how the tone goes up like a question; like a book you never stop rereading; like this process I’ve begun is never over. We left much more, left what still is the look of things, left what we felt at what we saw.

I take one picture. I slip my sunglasses in the pocket of my coat and turn toward home. I feel the evening coming on; the blackbird sits in the cedar-limbs and my legs feel strong. I’m looking up to catch a moment from the sky. And then, right there in my head, I write a letter to every person I’ve ever known. The letter says: I was the world in which I walked, and what I saw or heard or felt came not but from myself; and there I found myself more truly and more strange.

The Wallace Stevens Home

Map of The Wallace Stevens Walk